title: libigl Tutorial

author: Alec Jacobson, Daniele Pannozo and others

date: 20 June 2014

css: style.css

html header:

# Introduction

Libigl is an open source C++ library for geometry processing research and

development. Dropping the heavy data structures of tradition geometry

libraries, libigl is a simple header-only library of encapsulated functions.

This combines the rapid prototyping familiar to Matlab or Python programmers

with the performance and versatility of C++. The tutorial is a self-contained,

hands-on introduction to libigl. Via live coding and interactive examples, we

demonstrate how to accomplish various common geometry processing tasks such as

computation of differential quantities and operators, real-time deformation,

global parametrization, numerical optimization and mesh repair. Each section

of these lecture notes links to a cross-platform example application.

# Table of Contents

* [Chapter 1: Introduction to libigl]

* [Chapter 2: Discrete Geometric Quantities and

Operators](#chapter2:discretegeometricquantitiesandoperators)

* [201 Normals](#normals)

* [Per-face](#per-face)

* [Per-vertex](#per-vertex)

* [Per-corner](#per-corner)

* [202 Gaussian Curvature](#gaussiancurvature)

* [203 Curvature Directions](#curvaturedirections)

* [204 Gradient](#gradient)

* [204 Laplacian](#laplacian)

* [Mass matrix](#massmatrix)

* [Alternative construction of

Laplacian](#alternativeconstructionoflaplacian)

* [Chapter 3: Matrices and Linear Algebra](#chapter3:matricesandlinearalgebra)

* [301 Slice](#slice)

* [302 Sort](#sort)

* [Other Matlab-style functions](#othermatlab-stylefunctions)

* [303 Laplace Equation](#laplaceequation)

* [Quadratic energy minimization](#quadraticenergyminimization)

* [304 Linear Equality Constraints](#linearequalityconstraints)

* [305 Quadratic Programming](#quadraticprogramming)

* [Chapter 4: Shape Deformation](#chapter4:shapedeformation)

* [401 Biharmonic Deformation](#biharmonicdeformation)

* [402 Polyharmonic Deformation](#polyharmonicdeformation)

* [403 Bounded Biharmonic Weights](#boundedbiharmonicweights)

* [404 Dual Quaternion Skinning](#dualquaternionskinning)

* [405 As-rigid-as-possible](#as-rigid-as-possible)

* [406 Fast automatic skinning

transformations](#fastautomaticskinningtransformations)

# Chapter 2: Discrete Geometric Quantities and Operators

This chapter illustrates a few discrete quantities that libigl can compute on a

mesh. This also provides an introduction to basic drawing and coloring routines

in our example viewer. Finally, we construct popular discrete differential

geometry operators.

## Normals

Surface normals are a basic quantity necessary for rendering a surface. There

are a variety of ways to compute and store normals on a triangle mesh.

### Per-face

Normals are well defined on each triangle of a mesh as the vector orthogonal to

triangle's plane. These piecewise constant normals produce piecewise-flat

renderings: the surface appears non-smooth and reveals its underlying

discretization.

### Per-vertex

Storing normals at vertices, Phong or Gouraud shading will interpolate shading

inside mesh triangles to produce smooth(er) renderings. Most techniques for

computing per-vertex normals take an average of incident face normals. The

techniques vary with respect to their different weighting schemes. Uniform

weighting is heavily biased by the discretization choice, where as area-based

or angle-based weighting is more forgiving.

The typical half-edge style computation of area-based weights might look

something like this:

```cpp

N.setZero(V.rows(),3);

for(int i : vertices)

{

for(face : incident_faces(i))

{

N.row(i) += face.area * face.normal;

}

}

N.rowwise().normalize();

```

Without a half-edge data-structure it may seem at first glance that looping

over incident faces---and thus constructing the per-vertex normals---would be

inefficient. However, per-vertex normals may be _throwing_ each face normal to

running sums on its corner vertices:

```cpp

N.setZero(V.rows(),3);

for(int f = 0; f < F.rows();f++)

{

for(int c = 0; c < 3;c++)

{

N.row(F(f,c)) += area(f) * face_normal.row(f);

}

}

N.rowwise().normalize();

```

### Per-corner

Storing normals per-corner is an efficient an convenient way of supporting both

smooth and sharp (e.g. creases and corners) rendering. This format is common to

OpenGL and the .obj mesh file format. Often such normals are tuned by the mesh

designer, but creases and corners can also be computed automatically. Libigl

implements a simple scheme which computes corner normals as averages of

normals of faces incident on the corresponding vertex which do not deviate by a

specified dihedral angle (e.g. 20°).

## Gaussian Curvature

Gaussian curvature on a continuous surface is defined as the product of the

principal curvatures:

$k_G = k_1 k_2.$

As an _intrinsic_ measure, it depends on the metric and

not the surface's embedding.

Intuitively, Gaussian curvature tells how locally spherical or _elliptic_ the

surface is ( $k_G>0$ ), how locally saddle-shaped or _hyperbolic_ the surface

is ( $k_G<0$ ), or how locally cylindrical or _parabolic_ ( $k_G=0$ ) the

surface is.

In the discrete setting, one definition for a ``discrete Gaussian curvature''

on a triangle mesh is via a vertex's _angular deficit_:

$k_G(v_i) = 2π - \sum\limits_{j\in N(i)}θ_{ij},$

where $N(i)$ are the triangles incident on vertex $i$ and $θ_{ij}$ is the angle

at vertex $i$ in triangle $j$ [][#meyer_2003].

Just like the continuous analog, our discrete Gaussian curvature reveals

elliptic, hyperbolic and parabolic vertices on the domain.

## Curvature Directions

The two principal curvatures $(k_1,k_2)$ at a point on a surface measure how much the

surface bends in different directions. The directions of maximum and minimum

(signed) bending are call principal directions and are always

orthogonal.

Mean curvature is defined simply as the average of principal curvatures:

$H = \frac{1}{2}(k_1 + k_2).$

One way to extract mean curvature is by examining the Laplace-Beltrami operator

applied to the surface positions. The result is a so-called mean-curvature

normal:

$-\Delta \mathbf{x} = H \mathbf{n}.$

It is easy to compute this on a discrete triangle mesh in libigl using the cotangent

Laplace-Beltrami operator [][#meyer_2003].

```cpp

#include

#include

#include

...

MatrixXd HN;

SparseMatrix L,M,Minv;

igl::cotmatrix(V,F,L);

igl::massmatrix(V,F,igl::MASSMATRIX_TYPE_VORONOI,M);

igl::invert_diag(M,Minv);

HN = -Minv*(L*V);

H = (HN.rowwise().squaredNorm()).array().sqrt();

```

Combined with the angle defect definition of discrete Gaussian curvature, one

can define principal curvatures and use least squares fitting to find

directions [][#meyer_2003].

Alternatively, a robust method for determining principal curvatures is via

quadric fitting [][#pannozo_2010]. In the neighborhood

around every vertex, a best-fit quadric is found and principal curvature values

and directions are sampled from this quadric. With these in tow, one can

compute mean curvature and Gaussian curvature as sums and products

respectively.

This is an example of syntax highlighted code:

```cpp

#include

int main(int argc, char * argv[])

{

return 0;

}

```

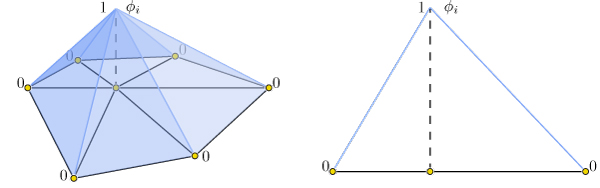

## Gradient

Scalar functions on a surface can be discretized as a piecewise linear function

with values defined at each mesh vertex:

$f(\mathbf{x}) \approx \sum\limits_{i=0}^n \phi_i(\mathbf{x})\, f_i,$

where $\phi_i$ is a piecewise linear hat function defined by the mesh so that

for each triangle $\phi_i$ is _the_ linear function which is one only at

vertex $i$ and zero at the other corners.

Thus gradients of such piecewise linear functions are simply sums of gradients

of the hat functions:

$\nabla f(\mathbf{x}) \approx

\nabla \sum\limits_{i=0}^n \nabla \phi_i(\mathbf{x})\, f_i =

\sum\limits_{i=0}^n \nabla \phi_i(\mathbf{x})\, f_i.$

This reveals that the gradient is a linear function of the vector of $f_i$

values. Because $\phi_i$ are linear in each triangle their gradient are

_constant_ in each triangle. Thus our discrete gradient operator can be written

as a matrix multiplication taking vertex values to triangle values:

$\nabla f \approx \mathbf{G}\,\mathbf{f},$

where $\mathbf{f}$ is $n\times 1$ and $\mathbf{G}$ is an $md\times n$ sparse

matrix. This matrix $\mathbf{G}$ can be derived geometrically, e.g.

[ch. 2][#jacobson_thesis_2013].

Libigl's `gradMat`**Alec: check name** function computes $\mathbf{G}$ for

triangle and tetrahedral meshes:

## Laplacian

The discrete Laplacian is an essential geometry processing tool. Many

interpretations and flavors of the Laplace and Laplace-Beltrami operator exist.

In open Euclidean space, the _Laplace_ operator is the usual divergence of gradient

(or equivalently the Laplacian of a function is the trace of its Hessian):

$\Delta f =

\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} +

\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2} +

\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial z^2}.$

The _Laplace-Beltrami_ operator generalizes this to surfaces.

When considering piecewise-linear functions on a triangle mesh, a discrete Laplacian may

be derived in a variety of ways. The most popular in geometry processing is the

so-called ``cotangent Laplacian'' $\mathbf{L}$, arising simultaneously from FEM, DEC and

applying divergence theorem to vertex one-rings. As a linear operator taking

vertex values to vertex values, the Laplacian $\mathbf{L}$ is a $n\times n$

matrix with elements:

$L_{ij} = \begin{cases}j \in N(i) &\cot \alpha_{ij} + \cot \beta_{ij},\\

j \notin N(i) & 0,\\

i = j & -\sum\limits_{k\neq i} L_{ik},

\end{cases}$

where $N(i)$ are the vertices adjacent to (neighboring) vertex $i$, and

$\alpha_{ij},\beta_{ij}$ are the angles opposite edge ${ij}$.

This oft

produced formula leads to a typical half-edge style implementation for

constructing $\mathbf{L}$:

```cpp

for(int i : vertices)

{

for(int j : one_ring(i))

{

for(int k : triangle_on_edge(i,j))

{

L(i,j) = cot(angle(i,j,k));

L(i,i) -= cot(angle(i,j,k));

}

}

}

```

Without a half-edge data-structure it may seem at first glance that looping

over one-rings, and thus constructing the Laplacian would be inefficient.

However, the Laplacian may be built by summing together contributions for each

triangle, much in spirit with its FEM discretization of the Dirichlet energy

(sum of squared gradients):

```cpp

for(triangle t : triangles)

{

for(edge i,j : t)

{

L(i,j) += cot(angle(i,j,k));

L(j,i) += cot(angle(i,j,k));

L(i,i) -= cot(angle(i,j,k));

L(j,j) -= cot(angle(i,j,k));

}

}

```

Libigl implements discrete "cotangent" Laplacians for triangles meshes and

tetrahedral meshes, building both with fast geometric rules rather than "by the

book" FEM construction which involves many (small) matrix inversions, cf.

**Alec: cite Ariel reconstruction paper**.

The operator applied to mesh vertex positions amounts to smoothing by _flowing_

the surface along the mean curvature normal direction. This is equivalent to

minimizing surface area.

![The `Laplacian` example computes conformalized mean curvature flow using the

cotangent Laplacian [#kazhdan_2012][].](images/cow-curvature-flow.jpg)

### Mass matrix

The mass matrix $\mathbf{M}$ is another $n \times n$ matrix which takes vertex

values to vertex values. From an FEM point of view, it is a discretization of

the inner-product: it accounts for the area around each vertex. Consequently,

$\mathbf{M}$ is often a diagonal matrix, such that $M_{ii}$ is the barycentric

or voronoi area around vertex $i$ in the mesh [#meyer_2003][]. The inverse of

this matrix is also very useful as it transforms integrated quantities into

point-wise quantities, e.g.:

$\nabla f \approx \mathbf{M}^{-1} \mathbf{L} \mathbf{f}.$

In general, when encountering squared quantities integrated over the surface,

the mass matrix will be used as the discretization of the inner product when

sampling function values at vertices:

$\int_S x\, y\ dA \approx \mathbf{x}^T\mathbf{M}\,\mathbf{y}.$

An alternative mass matrix $\mathbf{T}$ is a $md \times md$ matrix which takes

triangle vector values to triangle vector values. This matrix represents an

inner-product accounting for the area associated with each triangle (i.e. the

triangles true area).

### Alternative construction of Laplacian

An alternative construction of the discrete cotangent Laplacian is by

"squaring" the discrete gradient operator. This may be derived by applying

Green's identity (ignoring boundary conditions for the moment):

$\int_S \|\nabla f\|^2 dA = \int_S f \Delta f dA$

Or in matrix form which is immediately translatable to code:

$\mathbf{f}^T \mathbf{G}^T \mathbf{T} \mathbf{G} \mathbf{f} =

\mathbf{f}^T \mathbf{M} \mathbf{M}^{-1} \mathbf{L} \mathbf{f} =

\mathbf{f}^T \mathbf{L} \mathbf{f}.$

So we have that $\mathbf{L} = \mathbf{G}^T \mathbf{T} \mathbf{G}$. This also

hints that we may consider $\mathbf{G}^T$ as a discrete _divergence_ operator,

since the Laplacian is the divergence of gradient. Naturally, $\mathbf{G}^T$ is

$n \times md$ sparse matrix which takes vector values stored at triangle faces

to scalar divergence values at vertices.

# Chapter 3: Matrices and Linear Algebra

Libigl relies heavily on the Eigen library for dense and sparse linear algebra

routines. Besides geometry processing routines, libigl has a few linear algebra

routines which bootstrap Eigen and make Eigen feel even more like a high-level

algebra library like Matlab.

## Slice

A very familiar and powerful routine in Matlab is array slicing. This allows

reading from or writing to a possibly non-contiguous sub-matrix. Let's consider

the matlab code:

```matlab

B = A(R,C);

```

If `A` is a $m \times n$ matrix and `R` is a $j$-long list of row-indices

(between 1 and $m$) and `C` is a $k$-long list of column-indices, then as a

result `B` will be a $j \times k$ matrix drawing elements from `A` according to

`R` and `C`. In libigl, the same functionality is provided by the `slice`

function:

```cpp

VectorXi R,C;

MatrixXd A,B;

...

igl::slice(A,R,C,B);

```

`A` and `B` could also be sparse matrices.

Similarly, consider the matlab code:

```matlab

A(R,C) = B;

```

Now, the selection is on the left-hand side so the $j \times k$ matrix `B` is

being _written into_ the submatrix of `A` determined by `R` and `C`. This

functionality is provided in libigl using `slice_into`:

```cpp

igl::slice_into(B,R,C,A);

```

## Sort

Matlab and other higher-level languages make it very easy to extract indices of

sorting and comparison routines. For example in Matlab, one can write:

```matlab

[Y,I] = sort(X,1,'ascend');

```

so if `X` is a $m \times n$ matrix then `Y` will also be an $m \times n$ matrix

with entries sorted along dimension `1` in `'ascend'`ing order. The second

output `I` is a $m \times n$ matrix of indices such that `Y(i,j) =

X(I(i,j),j);`. That is, `I` reveals how `X` is sorted into `Y`.

This same functionality is supported in libigl:

```cpp

igl::sort(X,1,true,Y,I);

```

Similarly, sorting entire rows can be accomplished in matlab using:

```matlab

[Y,I] = sortrows(X,'ascend');

```

where now `I` is a $m$ vector of indices such that `Y = X(I,:)`.

In libigl, this is supported with

```cpp

igl::sortrows(X,true,Y,I);

```

where again `I` reveals the index of sort so that it can be reproduced with

`igl::slice(X,I,1,Y)`.

Analogous functions are available in libigl for: `max`, `min`, and `unique`.

### Other Matlab-style functions

Libigl implements a variety of other routines with the same api and

functionality as common matlab functions.

- `igl::any_of` Whether any elements are non-zero (true)

- `igl::cat` Concatenate two matrices (especially useful for dealing with Eigen

sparse matrices)

- `igl::ceil` Round entries up to nearest integer

- `igl::cumsum` Cumulative sum of matrix elements

- `igl::colon` Act like Matlab's `:`, similar to Eigen's `LinSpaced`

- `igl::cross` Cross product per-row

- `igl::dot` dot product per-row

- `igl::find` Find subscripts of non-zero entries

- `igl::floot` Round entries down to nearest integer

- `igl::histc` Counting occurrences for building a histogram

- `igl::hsv_to_rgb` Convert HSV colors to RGB (cf. Matlab's `hsv2rgb`)

- `igl::intersect` Set intersection of matrix elements.

- `igl::jet` Quantized colors along the rainbow.

- `igl::kronecker_product` Compare to Matlab's `kronprod`

- `igl::median` Compute the median per column

- `igl::mode` Compute the mode per column

- `igl::orth` Orthogonalization of a basis

- `igl::setdiff` Set difference of matrix elements

- `igl::speye` Identity as sparse matrix

## Laplace Equation

A common linear system in geometry processing is the Laplace equation:

$∆z = 0$

subject to some boundary conditions, for example Dirichlet boundary conditions

(fixed value):

$\left.z\right|_{\partial{S}} = z_{bc}$

In the discrete setting, this begins with the linear system:

$\mathbf{L} \mathbf{z} = \mathbf{0}$

where $\mathbf{L}$ is the $n \times n$ discrete Laplacian and $\mathbf{z}$ is a

vector of per-vertex values. Most of $\mathbf{z}$ correspond to interior

vertices and are unknown, but some of $\mathbf{z}$ represent values at boundary

vertices. Their values are known so we may move their corresponding terms to

the right-hand side.

Conceptually, this is very easy if we have sorted $\mathbf{z}$ so that interior

vertices come first and then boundary vertices:

$$\left(\begin{array}{cc}

\mathbf{L}_{in,in} & \mathbf{L}_{in,b}\\

\mathbf{L}_{b,in} & \mathbf{L}_{b,b}\end{array}\right)

\left(\begin{array}{c}

\mathbf{z}_{in}\\

\mathbf{L}_{b}\end{array}\right) =

\left(\begin{array}{c}

\mathbf{0}_{in}\\

\mathbf{*}_{b}\end{array}\right)$$

The bottom block of equations is no longer meaningful so we'll only consider

the top block:

$$\left(\begin{array}{cc}

\mathbf{L}_{in,in} & \mathbf{L}_{in,b}\end{array}\right)

\left(\begin{array}{c}

\mathbf{z}_{in}\\

\mathbf{z}_{b}\end{array}\right) =

\mathbf{0}_{in}$$

Where now we can move known values to the right-hand side:

$$\mathbf{L}_{in,in}

\mathbf{z}_{in} = -

\mathbf{L}_{in,b}

\mathbf{z}_{b}$$

Finally we can solve this equation for the unknown values at interior vertices

$\mathbf{z}_{in}$.

However, probably our vertices are not sorted. One option would be to sort `V`,

then proceed as above and then _unsort_ the solution `Z` to match `V`. However,

this solution is not very general.

With array slicing no explicit sort is needed. Instead we can _slice-out_

submatrix blocks ($\mathbf{L}_{in,in}$, $\mathbf{L}_{in,b}$, etc.) and follow

the linear algebra above directly. Then we can slice the solution _into_ the

rows of `Z` corresponding to the interior vertices.

### Quadratic energy minimization

The same Laplace equation may be equivalently derived by minimizing Dirichlet

energy subject to the same boundary conditions:

$\mathop{\text{minimize }}_z \frac{1}{2}\int\limits_S \|\nabla z\|^2 dA$

On our discrete mesh, recall that this becomes

$\mathop{\text{minimize }}_\mathbf{z} \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{G}^T \mathbf{D}

\mathbf{G} \mathbf{z} \rightarrow \mathop{\text{minimize }}_\mathbf{z} \mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{L} \mathbf{z}$

The general problem of minimizing some energy over a mesh subject to fixed

value boundary conditions is so wide spread that libigl has a dedicated api for

solving such systems.

Let's consider a general quadratic minimization problem subject to different

common constraints:

$$\mathop{\text{minimize }}_\mathbf{z} \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{z} +

\mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{B} + \text{constant},$$

subject to

$$\mathbf{z}_b = \mathbf{z}_{bc} \text{ and } \mathbf{A}_{eq} \mathbf{z} =

\mathbf{B}_{eq},$$

where

- $\mathbf{Q}$ is a (usually sparse) $n \times n$ positive semi-definite

matrix of quadratic coefficients (Hessian),

- $\mathbf{B}$ is a $n \times 1$ vector of linear coefficients,

- $\mathbf{z}_b$ is a $|b| \times 1$ portion of

$\mathbf{z}$ corresponding to boundary or _fixed_ vertices,

- $\mathbf{z}_{bc}$ is a $|b| \times 1$ vector of known values corresponding to

$\mathbf{z}_b$,

- $\mathbf{A}_{eq}$ is a (usually sparse) $m \times n$ matrix of linear

equality constraint coefficients (one row per constraint), and

- $\mathbf{B}_{eq}$ is a $m \times 1$ vector of linear equality constraint

right-hand side values.

This specification is overly general as we could write $\mathbf{z}_b =

\mathbf{z}_{bc}$ as rows of $\mathbf{A}_{eq} \mathbf{z} =

\mathbf{B}_{eq}$, but these fixed value constraints appear so often that they

merit a dedicated place in the API.

In libigl, solving such quadratic optimization problems is split into two

routines: precomputation and solve. Precomputation only depends on the

quadratic coefficients, known value indices and linear constraint coefficients:

```cpp

igl::min_quad_with_fixed_data mqwf;

igl::min_quad_with_fixed_precompute(Q,b,Aeq,true,mqwf);

```

The output is a struct `mqwf` which contains the system matrix factorization

and is used during solving with arbitrary linear terms, known values, and

constraint right-hand sides:

```cpp

igl::min_quad_with_fixed_solve(mqwf,B,bc,Beq,Z);

```

The output `Z` is a $n \times 1$ vector of solutions with fixed values

correctly placed to match the mesh vertices `V`.

## Linear Equality Constraints

We saw above that `min_quad_with_fixed_*` in libigl provides a compact way to

solve general quadratic programs. Let's consider another example, this time

with active linear equality constraints. Specifically let's solve the

`bi-Laplace equation` or equivalently minimize the Laplace energy:

$$\Delta^2 z = 0 \leftrightarrow \mathop{\text{minimize }}\limits_z \frac{1}{2}

\int\limits_S (\Delta z)^2 dA$$

subject to fixed value constraints and a linear equality constraint:

$z_{a} = 1, z_{b} = -1$ and $z_{c} = z_{d}$.

Notice that we can rewrite the last constraint in the familiar form from above:

$z_{c} - z_{d} = 0.$

Now we can assembly `Aeq` as a $1 \times n$ sparse matrix with a coefficient

$1$

in the column corresponding to vertex $c$ and a $-1$ at $d$. The right-hand side

`Beq` is simply zero.

Internally, `min_quad_with_fixed_*` solves using the Lagrange Multiplier

method. This method adds additional variables for each linear constraint (in

general a $m \times 1$ vector of variables $\lambda$) and then solves the

saddle problem:

$$\mathop{\text{find saddle }}_{\mathbf{z},\lambda}\, \frac{1}{2}\mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{Q} \mathbf{z} +

\mathbf{z}^T \mathbf{B} + \text{constant} + \lambda^T\left(\mathbf{A}_{eq}

\mathbf{z} - \mathbf{B}_{eq}\right)$$

This can be rewritten in a more familiar form by stacking $\mathbf{z}$ and

$\lambda$ into one $(m+n) \times 1$ vector of unknowns:

$$\mathop{\text{find saddle }}_{\mathbf{z},\lambda}\,

\frac{1}{2}

\left(

\mathbf{z}^T

\lambda^T

\right)

\left(

\begin{array}{cc}

\mathbf{Q} & \mathbf{A}_{eq}^T\\

\mathbf{A}_{eq} & 0

\end{array}

\right)

\left(

\begin{array}{c}

\mathbf{z}\\

\lambda

\end{array}

\right) +

\left(

\mathbf{z}^T

\lambda^T

\right)

\left(

\begin{array}{c}

\mathbf{B}\\

-\mathbf{B}_{eq}

\end{array}

\right)

+ \text{constant}$$

Differentiating with respect to $\left( \mathbf{z}^T \lambda^T \right)$ reveals

a linear system and we can solve for $\mathbf{z}$ and $\lambda$. The only

difference from

the straight quadratic

_minimization_ system, is that

this saddle problem system will not be positive definite. Thus, we must use a

different factorization technique (LDLT rather than LLT). Luckily, libigl's

`min_quad_with_fixed_precompute` automatically chooses the correct solver in

the presence of linear equality constraints.

## Quadratic Programming

We can generalize the quadratic optimization in the previous section even more

by allowing inequality constraints. Specifically box constraints (lower and

upper bounds):

$\mathbf{l} \le \mathbf{z} \le \mathbf{u},$

where $\mathbf{l},\mathbf{u}$ are $n \times 1$ vectors of lower and upper

bounds

and general linear inequality constraints:

$\mathbf{A}_{ieq} \mathbf{z} \le \mathbf{B}_{ieq},$

where $\mathbf{A}_{ieq}$ is a $k \times n$ matrix of linear coefficients and

$\mathbf{B}_{ieq}$ is a $k \times 1$ matrix of constraint right-hand sides.

Again, we are overly general as the box constraints could be written as

rows of the linear inequality constraints, but bounds appear frequently enough

to merit a dedicated api.

Libigl implements its own active set routine for solving _quadratric programs_

(QPs). This algorithm works by iteratively "activating" violated inequality

constraints by enforcing them as equalities and "deactivating" constraints

which are no longer needed.

After deciding which constraints are active each iteration simple reduces to a

quadratic minimization subject to linear _equality_ constraints, and the method

from the previous section is invoked. This is repeated until convergence.

Currently the implementation is efficient for box constraints and sparse

non-overlapping linear inequality constraints.

Unlike alternative interior-point methods, the active set method benefits from

a warm-start (initial guess for the solution vector $\mathbf{z}$).

```cpp

igl::active_set_params as;

// Z is optional initial guess and output

igl::active_set(Q,B,b,bc,Aeq,Beq,Aieq,Bieq,lx,ux,as,Z);

```

![The example `QuadraticProgramming` uses an active set solver to optimize

discrete biharmonic kernels at multiple scales [#rustamov_2011][].](images/cheburashka-multiscale-biharmonic-kernels.jpg)

# Chapter 4: Shape Deformation

Modern mesh-based shape deformation methods satisfy user deformation

constraints at handles (selected vertices or regions on the mesh) and propagate

these handle deformations to the rest of shape _smoothly_ and _without removing

or distorting details_. Libigl provides implementations of a variety of

state-of-the-art deformation techniques, ranging from quadratic mesh-based

energy minimizers, to skinning methods, to non-linear elasticity-inspired

techniques.

## Biharmonic Deformation

The period of research between 2000 and 2010 produced a collection of

techniques that cast the problem of handle-based shape deformation as a

quadratic energy minimization problem or equivalently the solution to a linear

partial differential equation.

There are many flavors of these techniques, but

a prototypical subset are those that consider solutions to the bi-Laplace

equation, that is biharmonic functions [#botsch_2004][]. This fourth-order PDE provides

sufficient flexibility in boundary conditions to ensure $C^1$ continuity at

handle constraints (in the limit under refinement) [#jacobson_mixed_2010][].

### Biharmonic surfaces

Let us first begin our discussion of biharmonic _deformation_, by considering

biharmonic _surfaces_. We will casually define biharmonic surfaces as surface

whose _position functions_ are biharmonic with respect to some initial

parameterization:

$\Delta \mathbf{x}' = 0$

and subject to some handle constraints, conceptualized as "boundary

conditions":

$\mathbf{x}'_{b} = \mathbf{x}_{bc}.$

where $\mathbf{x}'$ is the unknown 3D position of a point on the surface. So we are

asking that the bi-Laplace of each of spatial coordinate functions to be zero.

In libigl, one can solve a biharmonic problem like this with `igl::harmonic`

and setting $k=2$ (_bi_-harmonic):

```cpp

// U_bc contains deformation of boundary vertices b

igl::harmonic(V,F,b,U_bc,2,U);

```

This produces smooth surfaces that interpolate the handle constraints, but all

original details on the surface will be _smoothed away_. Most obviously, if the

original surface is not already biharmonic, then giving all handles the identity

deformation (keeping them at their rest positions) will **not** reproduce the

original surface. Rather, the result will be the biharmonic surface that does

interpolate those handle positions.

Thus, we may conclude that this is not an intuitive technique for shape

deformation.

### Biharmonic deformation fields

Now we know that one useful property for a deformation technique is "rest pose

reproduction": applying no deformation to the handles should apply no

deformation to the shape.

To guarantee this by construction we can work with _deformation fields_ (ie.

displacements)

$\mathbf{d}$ rather

than directly with positions $\mathbf{x}. Then the deformed positions can be

recovered as

$\mathbf{x}' = \mathbf{x}+\mathbf{d}.$

A smooth deformation field $\mathbf{d}$ which interpolates the deformation

fields of the handle constraints will impose a smooth deformed shape

$\mathbf{x}'$. Naturally, we consider _biharmonic deformation fields_:

$\Delta \mathbf{d} = 0$

subject to the same handle constraints, but rewritten in terms of their implied

deformation field at the boundary (handles):

$\mathbf{d}_b = \mathbf{x}_{bc} - \mathbf{x}_b.$

Again we can use `igl::harmonic` with $k=2$, but this time solve for the

deformation field and then recover the deformed positions:

```cpp

// U_bc contains deformation of boundary vertices b

D_bc = U_bc - igl::slice(V,b,1);

igl::harmonic(V,F,b,D_bc,2,D);

U = V+D;

```

#### Relationship to "differential coordinates" and Laplacian surface editing

Biharmonic functions (whether positions or displacements) are solutions to the

bi-Laplace equation, but also minimizers of the "Laplacian energy". For

example, for displacements $\mathbf{d}$, the energy reads

$\int\limits_S \|\Delta \mathbf{d}\|^2 dA.$

By linearity of the Laplace(-Beltrami) operator we can reexpress this energy in

terms of the original positions $\mathbf{x}$ and the unknown positions

$\mathbf{x}' = \mathbf{x} - \mathbf{d}$:

$\int\limits_S \|\Delta (\mathbf{x}' - \mathbf{x})\|^2 dA = \int\limits_S \|\Delta \mathbf{x}' - \Delta \mathbf{x})\|^2 dA.$

In the early work of Sorkine et al., the quantities $\Delta \mathbf{x}'$ and

$\Delta \mathbf{x}$ were dubbed "differential coordinates" [#sorkine_2004][].

Their deformations (without linearized rotations) is thus equivalent to

biharmonic deformation fields.

## Polyharmonic deformation

We can generalize biharmonic deformation by considering different powers of

the Laplacian, resulting in a series of PDEs of the form:

$\Delta^k \mathbf{d} = 0.$

with $k\in{1,2,3,\dots}$. The choice of $k$ determines the level of continuity

at the handles. In particular, $k=1$ implies $C^0$ at the boundary, $k=2$

implies $C^1$, $k=3$ implies $C^2$ and in general $k$ implies $C^{k-1}$.

```cpp

int k = 2;// or 1,3,4,...

igl::harmonic(V,F,b,bc,k,Z);

```

## Bounded Biharmonic Weights

In computer animation, shape deformation is often referred to as "skinning".

Constraints are posed as relative rotations of internal rigid "bones" inside a

character. The deformation method, or skinning method, determines how the

surface of the character (i.e. its skin) should move as a function of the bone

rotations.

The most popular technique is linear blend skinning. Each point on the shape

computes its new location as a linear combination of bone transformations:

$\mathbf{x}' = \sum\limits_{i = 0}^m w_i(\mathbf{x}) \mathbf{T}_i

\left(\begin{array}{c}\mathbf{x}_i\\1\end{array}\right),$

where $w_i(\mathbf{x})$ is the scalar _weight function_ of the ith bone evaluated at

$\mathbf{x}$ and $\mathbf{T}_i$ is the bone transformation as a $4 \times 3$

matrix.

This formula is embarassingly parallel (computation at one point does not

depend on shared data need by computation at another point). It is often

implemented as a vertex shader. The weights and rest positions for each vertex

are sent as vertex shader _attribtues_ and bone transformations are sent as

_uniforms_. Then vertices are transformed within the vertex shader, just in

time for rendering.

As the skinning formula is linear (hence its name), we can write it as matrix

multiplication:

$\mathbf{X}' = \mathbf{M} \mathbf{T},$

where $\mathbx{X}'$ is $n \times 3$ stack of deformed positions as row

vectors, $\mathbf{M}$ is a $n \times m\cdot dim$ matrix containing weights and

rest positions and $\mathbf{T}$ is a $m\cdot (dim+1) \times dim$ stack of

transposed bone transformations.

Traditionally, the weight functions $w_j$ are painted manually by skilled

rigging professionals. Modern techniques now exist to compute weight functions

automatically given the shape and a description of the skeleton (or in general

any handle structure such as a cage, collection of points, selected regions,

etc.).

Bounded biharmonic weights are one such technique that casts weight computation

as a constrained optimization problem [#jacobson_2011][]. The weights enforce

smoothness by minimizing a smoothness energy: the familiar Laplacian energy:

$\sum\limits_{i = 0}^m \int_S (\Delta w_i)^2 dA$

subject to constraints which enforce interpolation of handle constraints:

$w_i(\mathbf{x}) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{ if } \mathbf{x} \in H_i\\ 0 & \text{ otherwise }

\end{cases},$

where $H_i$ is the ith handle, and constraints which enforce non-negativity,

parition of unity and encourage sparsity:

$0\le w_i \le 1$ and $\sum\limits_{i=0}^m w_i = 1.$

This is a quadratic programming problem and libigl solves it using its active

set solver or by calling out to Mosek.

[#botsch_2004]: Matrio Botsch and Leif Kobbelt. "An Intuitive Framework for

Real-Time Freeform Modeling," 2004.

[#jacobson_thesis_2013]: Alec Jacobson,

_Algorithms and Interfaces for Real-Time Deformation of 2D and 3D Shapes_,

2013.

[#jacobson_2011]: Alec Jacobson, Ilya Baran, Jovan Popović, and Olga Sorkin.

"Bounded Biharmonic Weights for Real-Time Deformation," 2011.

[#jacobson_mixed_2010]: Alec Jacobson, Elif Tosun, Olga Sorkine, and Denis

Zorin. "Mixed Finite Elements for Variational Surface Modeling," 2010.

[#kazhdan_2012]: Michael Kazhdan, Jake Solomon, Mirela Ben-Chen,

"Can Mean-Curvature Flow Be Made Non-Singular," 2012.

[#meyer_2003]: Mark Meyer, Mathieu Desbrun, Peter Schröder and Alan H. Barr,

"Discrete Differential-Geometry Operators for Triangulated

2-Manifolds," 2003.

[#pannozo_2010]: Daniele Pannozo, Enrico Puppo, Luigi Rocca,

"Efficient Multi-scale Curvature and Crease Estimation," 2010.

[#rustamov_2011]: Raid M. Rustamov, "Multiscale Biharmonic Kernels", 2011.

[#sorkine_2004]: Olga Sorkine, Yaron Lipman, Daniel Cohen-Or, Marc Alexa,

Christian Rössl and Hans-Peter Seidel. "Laplacian Surface Editing," 2004.